Despite extraordinarily low interest rates that would seem to have nowhere to go but up, some investment managers contend that fixed-income markets were offering some solid opportunities heading into 2016.

A key variable in that outlook is U.S. monetary policy. Ever since the Federal Reserve set the target for its benchmark federal funds rate near 0 percent seven years ago, investors have been speculating about when it would reverse that decision—and what the impact would be on the fixed-income markets.

They’re still waiting for a definitive answer.

Heading into 2015, it was widely anticipated the Fed would raise the fed funds target soon—perhaps as early as June 2015. But as the U.S. economy continued to grow in fits and starts, and inflation remained well below the Fed’s target for that metric, the Fed declined to take action. By mid-October, when the SVIA held its annual Fall Forum in Washington, D.C., it was no longer clear whether the Fed would act by the end of the year.

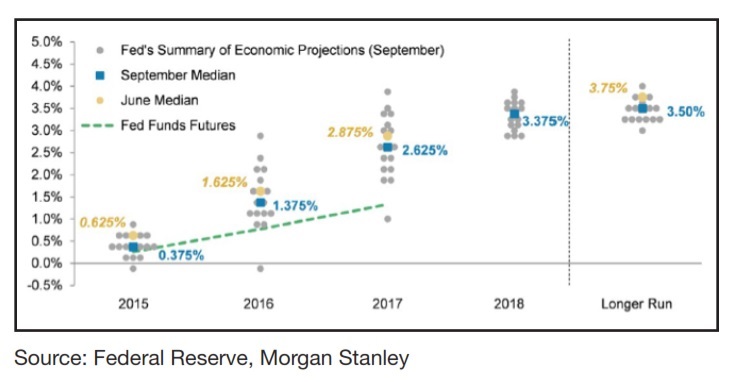

A key stumbling block for the Fed has been inflation. If it remains too far below the Fed’s target of 2 percent, some Fed governors worry that raising short-term interest rates could jeopardize the economy’s tenuous recovery. The Fed now doesn’t expect inflation to hit 2 percent until 2018, and its members are all over the map on where they expect the fed funds rate to be leading up to that point. The highest forecast is 4 percent in 2017, and the lowest for that year is just 1 percent.

In a panel discussion of the interest-rate outlook during the SVIA 2015 Fall Forum, Erol Sonderegger, a principal at Galliard Capital Management, suggested that the Fed’s wide-ranging expectations may be becoming counterproductive, damaging the Fed’s credibility in terms of understanding where the economy is heading and contributing to volatility in the financial markets.

Robert Tipp, managing director, chief investment strategist and head of global bonds for Prudential Fixed Income, added that the Fed’s decision not to hike short-term interest rates to that point may have reflected, to some degree, an “owning up” to the fact that it had been unduly optimistic about the economy’s strength heading into the year.

Tipp said that as interest rates have moved lower rather than higher, more reasons have “piled up” for them to stay low. The U.S. economy is growing only moderately. The economies of Japan and Europe are “okay by their standards” but growing even more slowly. And Europe continues to face difficult economic problems, including very high unemployment rates. Meanwhile, Tipp said, the picture in many emerging markets is even worse. He shared a chart noting that China’s growth rate has been falling for several years now, from 7.8 percent in 2012 to 7.4 percent last year. The chart also showed that Tipp expects China’s economy to grow at only about a 5.4 percent rate this year—below the consensus view—and 5.2 percent in 2016. (This forecast preceded China’s report in late October that its economy grew at only a 6.9 percent rate in the third quarter, its slowest pace since the global financial crisis.)

Dana Emery, president, CEO and a director of Dodge & Cox Funds, said she sees signs of improvement in the U.S. economy, with favorable developments in the housing market, in the number of household formations, in auto sales, and in declining energy prices that are helping consumers. While wage growth has been anemic despite declines in the unemployment rate, she added, improvements in the number of long-term unemployed suggest that wages might finally start to strengthen. Still, she observed, business spending has remained anemic lately, as has corporate revenue growth. Combining all that, Emery said she expects continued moderate economic growth in the U.S., with inflation eventually starting to pick up.

Even so, Steven Ruth, client portfolio manager for Voya Investment Management, said he doesn’t foresee interest rates jumping sharply. “At some point, we’ll have liftoff,” he said. “But I think there are enough headwinds out there, and a lack of confidence in inflation going forward, that the Fed can keep rates lower for longer, and even when they make a move take a very slow, deliberate trajectory.” As long as the Fed communicates that message and can deliver on it, Ruth added, it may be able to mitigate some of the volatility that rising rates would otherwise have on the financial markets.

In looking at how different sectors of the fixed-income markets might perform in this environment, Tipp argued that the outlook for fixed-income “looks very good.”

The bulk of returns aren’t likely to come in the form of capital gains, which would require rates to fall, but rather by taking advantage of the spread between yields on U.S. Treasury bonds and taxable bonds. While spreads are not as wide as they were during the 2008 financial crisis, he noted, they are quite wide relative to the level of yields, and that’s made spread products attractive not just to U.S. investors but also to foreign investors. Foreign investors also are being drawn to the U.S. Treasury market, he added, because Treasuries are yielding far more than other sovereign bonds. Continued purchases of Treasuries by international investors could help to moderate longer-term Treasury yields, he said, even if the Fed starts to raise short-term rates.

Tipp, Emery and Sonderegger all emphasized the importance of doing sound credit research before buying any spread products, cautioning that the opportunities aren’t equal across the marketplace.